Author: Sachin Bhardwaj Lock

The figures are truly shocking. The probability of dying from snakebites before reaching the age of 70 is an astonishing 1 in 250. Snakebites have claimed an estimated 1.2 million over the last 20 years in India. A quarter of those have been children, over the last two decades.

These are the findings of an ambitious new study, by the Centre for Global Health Research (CGHR). The study aimed to catalog the scope of India’s snakebite epidemic. Data-led solutions in the near future is certainly a possibility. In this, the first of a series of short articles examining key developments, issues, and conservation strategies in the field of herpetology (the study of reptiles and amphibians), we will take a close look at the deadly disease. In the next installment, we will be finding out more about those trying to fight.

Snakebites – A Short Story

It’s a warm late July evening in a village not too far from Kudra, Bihar. The last glow of the setting sun has almost entirely been lost below the horizon. Farmers returning from a long day in the fields find the ground beneath their feet softened by the monsoon rains. On one of the now darkened paths, a crowd has gathered around one of the senior figures in the village, a man in his 50s, who has apparently had a bad fall. He clutches his ankle and cries out in agony. It soon becomes clear that this was no fall; the man has been bitten by Russell’s viper and those around him know that his prospects of survival are now extremely bleak.

Some of those gathered spring into action with desperate suggestions of tying a rope around the leg or sucking out the venom. Eventually, they agree to take the man to the local healer. As they pull him to his feet and begin to rush him into the village, they bump into one of the younger residents returning from his job in the town. He insists that the only treatment for snakebite is antivenom, which can only be administered in a hospital. After much disagreement, eventually, the victim himself decides that this is the course he wants to take and so he is bundled into a car to make the two-hour drive along pitch-black dirt roads to the nearest hospital.

When he eventually arrives, the doctors question him to try to understand what kind of snake this man has been bitten by – many older antivenoms are specific, and even the right one could cause a fatal allergic reaction. From his description, one of the doctors uses her phone to determine that he has most likely been bitten by Russell’s viper and administers the appropriate antivenom, with the full knowledge that these treatments have been completely ineffective in the last ten cases she has seen. Even if, against severe odds, the man does survive, she knows that the haemotoxic (causing blood to clot, especially in the vessels connecting the heart to the longs) venom coursing through his veins could well leave him with a life-long disability, potentially even the loss of his leg, effectively a death sentence for a man who relies on manual labour for his entire livelihood.

The Problems – Snakebites in Farms

The story above is an ‘idealised’ snakebite, using the data from the Million Deaths Study to create the most likely scenario in which a bite could occur. Let’s pick it apart and analyse, piece by piece, what went wrong and why.

We’ll begin with the walk through the fields. We know that farming areas, particularly those that produce grain, attract the rodents on which snakes feed in large numbers, which are where the most snakebites occur. The study shows that 6 pm to midnight is the most common time for snakebite to occur, with almost a third of bites occurring during this six-hour window. This is most likely the result of a combination of two factors; people are still active outside as they return home or socialise and a lack of lighting in rural areas means that visibility is highly reduced or non-existent. Just under half of India’s snakebites occur in the monsoon season from June to September as a result of harvest activities in tall crop fields, the height of the growing plants again reducing visibility.

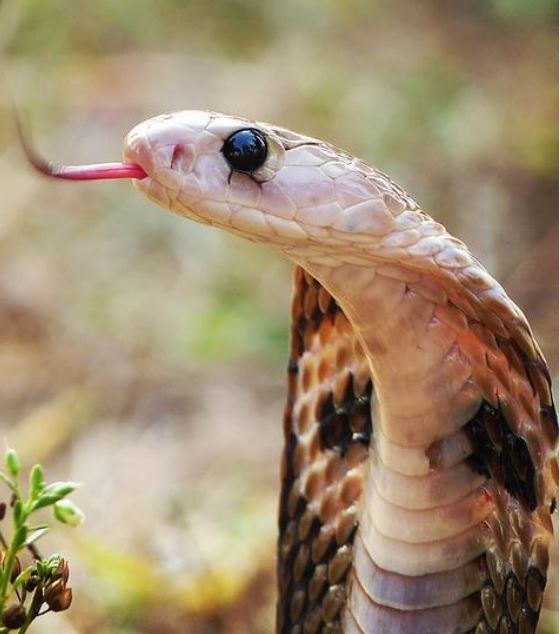

As for the snake itself, the Russell’s viper, Daboia ruselii, is a member of India’s ‘Big Four’. This includes the Indian cobra, saw-scaled viper, and common krait. Combined, they are responsible for over three-quarters of snakebites in India. Russel’s Viper has a wide distribution across Southern Asia. Coupled with its affinity for farm-loving rodents, often brings it into conflict with humans. No wonder, the species is responsible for 43% of snakebites in India. The species’ ambush hunting strategy utilizes its excellent camouflage. This effectively renders it invisible to all but the keenest eyes. This explains why 77% of all India’s snakebites are to the legs. The oblivious passerby may step on an unexpecting snake, triggering a snakebite in response.

The stage of first aid consultation immediately following the bite is a crucial. Time-consuming and misinformed judgments jeopardies the ability to successfully heal the patient. In such scenarios, despite their genuine intentions, the layman may provide incorrect advice. Unfortunately, this can cause a great deal of harm to and even endanger the life of a snakebite victim.

First Aid Misconceptions

Tying something around the limb to prevent the spread of venom seems like a logical solution. However, in reality, any such tourniquet that prevents the flow of blood can cause the death of the isolated flesh. Moreover, this may potentially result in an unnecessary amputation. This is particularly if the bite was ‘dry’ or if the biting species was not dangerous. Contrary to common beliefs, most venomous snakes do not always inject venom in a self-defense ‘warning’ bite. Venom production is energy-intensive and time-consuming. Additionally, some doctors have reported a ‘jolt’ of venom shooting rapidly through the body when the pressure building behind the tourniquet is released as it is untied. This causes the effects of the venom to be felt more widely and rapidly than if it had been circulated normally by the body.

Attempting to suck the venom out of the wound is not directly harmful. Nonetheless, it is almost completely ineffective and wastes vital time. Some species, such as cobras, inject neurotoxic venom. This impacts the body’s nervous system, including the heart and lungs. These venoms can be fatal in a matter of hours. Another unfortunately common technique, cutting around the bite site. This is in attempt to ‘squeeze’ the venom out. This is not only equally ineffective, but also dangerous. It creates a potential site of infection. In extreme cases, this causes sepsis as the tools used to create such cuts are rarely sterile.

Walking is also problematic for the victim. This as increases the rate of circulation of venom within their body, particularly if the bite is on one of the limbs. Numerous studies have demonstrated that antivenom is the only truly effective treatment for venomous snakebites. The local healer’s ‘medicine’ is likely to be totally ineffective. If the above methods are used, these cures can even be harmful. Successful cases of ‘recoveries’ by such healers are usually fluke. These cures are more than likely the result of the dry bites we’ve already discussed. Unfortunately, such misconceptions can dangerously increase reliance on traditional ‘medicine’ as a first treatment. Contrary to popular belief, it is challenging to identify venomous snakes.

By now it should hopefully be apparent that the simplest solution to the problems we’ve discussed so far is, by and large, education. We’ll be examining this and other solutions, along with the problems posed once a victim does get to a hospital, next time. Fortunately, with the rise of citizen science software, there seems to be light at the end of the tunnel. The Big4 Mapper application attempts to not only identify conflict hotspots, but facilitate communications between villagers and snake rescuers. This is essential to prevent fatal injuries.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this installment of the Think Wildlife Foundation Blog. Please do leave your thoughts and suggestions in the comments below and we’ll do our best to respond.

Help us Help Them! Think Wildlife Foundation is a non profit organization with various conservation initiatives. Our most prominent campaign is our Caring for Pari intiative. Pari is a rehabilitated elephant at the Wildlife SoS Hospital. 25% of the profits from our store are donated to the elephant hospital for Pari. Other than buying our wonderful merchandise, you could donate directly to our Caring For Pari fundraiser.